Religion and Maternal Grief

Danielle Griego, PhD | December 20, 2019

“Saint Thomas, long ago you returned my son to me. Why did you give him back, only to cause maternal grief? You cured the illness that caused miserable pain. Woe is me! How have I sinned? What command have I gone against to endure bereavement.”(1)

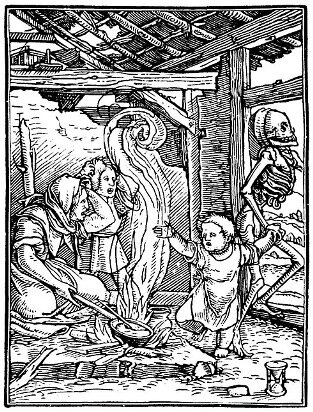

Medieval miracle stories, which were collections of miracle accounts used to promote an individual’s sanctity, also contained numerous descriptions of child death and maternal grief. Religious authors often employed female grief in these accounts to highlight their expectations for parental duties, specifically the notion that women were responsible for the safety of children around the domestic realm. Women were often depicted as grieving publicly in order to showcase the guilt that they experienced for not protecting their offspring from external threats, such as accidents that took place while performing household chores.

Miracle stories also emphasized the idea that mothers were responsible for keeping their children safe from divine punishment. For example, the excerpt above is taken from the Thomas Becket miracle collection, which was written by Benedict of Peterborough in the twelfth century. The story centers around a woman named Matilda, who mourns, in front of her entire household, the loss of her son after he succumbs to a ruptured hernia. In this miracle, Matilda explains that her son had previously suffered from an illness and was cured by the divine intervention of Saint Thomas Becket. However, later the boy was afflicted by complications of a hernia, which ultimately caused his death. Matilda wonders why Thomas Becket healed the child only to have him suffer later on. What is interesting about this miracle is that towards the end of the lament Matilda assumes blame for the death, even though her son dies from sickness and not an accident that she could have technically prevented from happening. She states that the holy man must be punishing her for sins that she has committed and goes on to ask forgiveness. Once this supplication is made, the boy is eventually revived by Saint Becket. This account demonstrates that mothers were not only expected to save children from physical hazards around the household, but also spiritual dangers, including the spiritual repercussions of unholy deeds. Benedict of Peterborough uses Matilda’s grief to bring this message to the forefront of the miracle. Matilda cries out and publicly chastises herself for sinning. It is not until she offers to conduct penance in exchange for the child’s recovery that the boy regains consciousness. Medieval mothers were expected to not only be good members of their parish, but also emulate holy figures and their deeds, such as the Virgin Mary, the paradigm of motherhood. Matilda, in the eyes of the miracle writer, does not fit this mold and her child suffers the consequences.

The sentiment that medieval women were expected to fulfill religious duties (and be free of sin) in order to protect their children is even seen in priest manuals. Priests manuals contained instructions for priests on how to advise members of their parish on certain topics. When discussing pregnancy and childbirth, John Mirk, an Augustinian Canon, said that priests should advise pregnant women to go to confession and receive the Eucharist before labor. In lines 77-84, he pointed out:

Women that are with child / Although most of them are taught what they should do / When the time is at hand / Tell them to do all and some: Teach them to come and confess themselves clean / And also have them receive communion before God / because of the dread of peril that may befall [during labor].(2)

Here, Mirk points out the dangers of childbirth. Because complications during labor were common, Mirk advised that women be spiritually prepared in case death occurred. What is more telling, women were expected to receive the sacraments to ensure the well-being of their unborn children.

Miracle stories, then, can tell us a lot about expectations for medieval women in regard to childrearing and religious obligations. Women were not only expected to maintain the economy of the household, but were also supposed to protect their children from physical and spiritual threats. Spiritual threats could come in the form of not following religious protocol, such as not receiving sacraments before child birth, and also in the form of committing sins, as shown in the miracle about Matilda and her son. Authors of miracle stories, like Benedict of Peterborough, used the emotion of grief to highlight this sentiment and reinforce the idea that a woman’s spiritual identity affected the well-being of her offspring.

Notes

Benedict of Peterborough, Materials for the History of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, Canonoized by Pope Alexander III, A. D. 1173, Vol. 2. Edited by James Robertson. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 229. During the Middle Ages, most miracle stories were written in Latin. The following is the original Latin text from the Thomas Becket miracle collection: “Sancte Thoma, pridem puerum mihi reddidist; cur ad maternum luctum reddere voluisti? Morbum, quo misere cruciabatur, curasti; væ mihi, quo nunc peccato, qua transgressione mandatorum, damnor orbitate?”

John Mirk, Instructions for Parish Priests, ed. Edward Peacock (London: English Text Society, 1902), lines 77-84: “Wymmen that ben wyth chyde also / Thow moste hem teche how þey schule do. / Whenne here tyme ys neghe y-come, / Bydde hem do thus alle & some: Theche hem to come & schryue hem clene, / And also hosele hem bothe et ene, / For drede of perele that may be-falle.”

About the Author

Dr. Danielle Griego was born and raised in Belen, NM, and received her PhD in history from the University of Missouri, where she specialized in medieval history. Griego also holds a bachelor's degree in anthropology and archaeology from the University of New Mexico and a master of philosophy in medieval history from the University of Cambridge.