Nana's Wig

Erica Gerald Mason | November 23, 2020

This article is part of The Death Gap Series, a collaboration between The Order Of The Good Death and The Collective For Radical Death Studies. The series examines the various ways in which systemic racism impacts the way BIPOC communities experience death and access end-of-life care.

It’s Saturday morning in the summertime, and you are seven. Your grandmother takes you to Fulton Street in Brooklyn. She’s shopping for a wig, and she’d like you to hurry up. Saturday is the worst day to buy wigs. You and your sister follow her as she surveys the wigs in the shop. As in all things, but especially wig shopping, your Nana takes her time. After a million light years, or perhaps 20 minutes, your grandmother chooses a chocolate brown wig and motions to the shopkeeper. “Aren’t you going to try it on?,” you ask, but she shakes her head. “I know this head better than anyone. I know what looks good on it.”

Later that night, at dinner, your grandmother debuts her new wig. She’s right, of course. She looks beautiful.

It’s another Saturday morning in the summertime, and you are ten. You are sitting on the sofa, turning the pages in your grandmother’s photo album while she says good morning to her fish by tapping the aquarium glass with her manicured fingernails. You point to a picture of a nondescript building and ask about it. Your grandmother peers over your shoulder and says, “That’s the funeral parlor.” They called them parlors back when she was a little girl. “The last good one. It’s closed now.” You ask her what made it good. She takes a pull on her cigarette before she answers. “They knew how to make us look good.” Your grandmother doesn’t say who ‘us’ is, but you know it’s Us. It’s Black folk.

It is summertime two years later, and she is watching you comb your hair. You are rushing, but there are more knots than usual. The knots crackle as your comb moves through them. You are fixing your hair before you, your sister, your mother, and your grandmother go to the mall. The shopping center is only three blocks from your house, but you have to look presentable before you leave your apartment. There’s a new wig on your grandmother’s head, this one with an auburn tint. Nana scratches her hairline under the wig, careful not to disturb her appearance. She’s always been a beauty, that one.

You place the bulk of your hair year in your right fist and use your other hand to position an elastic until your ponytail is sufficiently puffy. Your grandmother stops you.

“How long has it been since you’ve had your hair done?”

“A while,” you say, and it’s the truth. You’re saving money to go to the hairdresser, but you don’t have enough just yet.

Your grandmother shuffles over to get her handbag from the kitchen. She unclasps the bag and pulls out two $20 bills.

“Here,” she says. “Get your hair done.”

“You didn’t have to do that,” you say, and you mean that, too. “I’ll have enough money in a few weeks.”

She waves your protest away as she shuffles back to her chair.

“Remember, half of that hair on your head is mine now, so take good care of it.”

You fold the money into your back pocket and go to the mall with your family. You don’t remember what you bought, or how long you stayed there. That part of the recollection slid into the sea of the forgotten a long time ago.

Years pass. Decades.

You go to funerals. Not many, but enough to see what your grandmother meant about the ‘good ones’. Beautiful brown skin turned gray by the wrong makeup. Lipstick that no Black woman would ever wear. And the worst, wigs that lay askew. Tugged on as an afterthought, like a child who has been told by a parent to put on a scarf before he goes outside to play. That is to say, with a tinge of resentment and a handful of carelessness.

Your grandmother wears wigs; a new one every time you visit her. Some days it’s an afro, other days its tight ringlets. Nana likes to change things up.

One time, you get your hair straightened, and you show your grandmother. “It ain’t got no curl,” she sniffs. “You’ve gotta have some curl, even if it’s just a little.”

You’re a teenager now, so you don’t want to take her advice, but when she walks away, you grab a curling iron and make a few curls.

At dinner, she smiles at you and points at her wig. “I know what I’m talking about.”

You smile back, because you know she’s right.

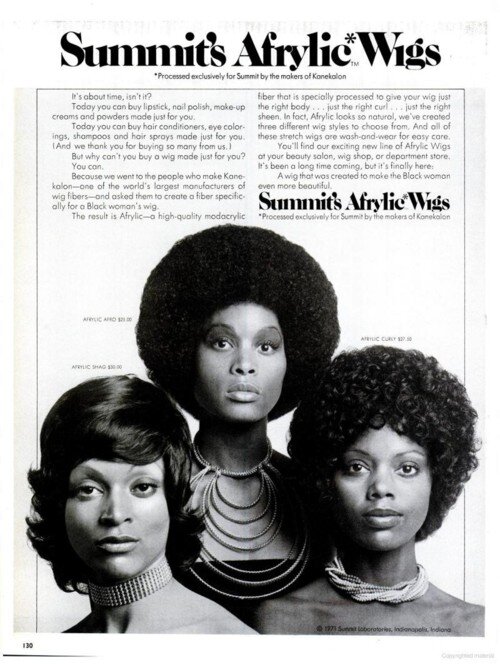

1960s vintage advertisement for Star Glow wigs

Your grandmother is sick. She has circulation problems in her legs, and her doctor recommends surgery. It is December of 2007 when she agrees to the surgery. Your aunt, your sister and you drive from Georgia to Indiana to be with your mother and grandmother for the surgery. The nurse wheels her away for the operation and you sit in the waiting room eating M&M’s and giggling with your sister. Things are good, but they go bad quickly. In the hospital, the nurse pulls your family to the side and tells you to wait for the surgeon in a small room. The doctor tells you there have been complications, but your grandmother is resting in an ICU. She’s intubated, but awake. You gather your things and go visit her, and a single tear slides out of her left eye and slides down her cheek. You kiss her, fix her wig, and walk away, the bag of M&M’s balled up in your right fist. You decide you hate M&Ms while you stand in the hallway and cry.

You don’t think things can get worse, but they do. The nurse mentions your grandmother’s breast cancer as if it’s a known fact. It’s not. Sleep happens on the floor in hospital conference rooms and on empty gurneys in hallways. The doctor comes in and briefs you often. His cellphone rings as he talks to you. He turns it off without looking to see who’s calling. You appreciate that. His ringtone is the Batman theme. You decide you now hate Batman as well.

You are a zombie, but you don’t know it. You don’t know what to do, so you fix her wig whenever you can.

You go back to Georgia, but then come right back. At some point, the United States swears in its first Black president. Your grandmother, scheduled for another surgery, misses the moment. You go back to Georgia again. Then come right back again. This time, for the final time.

She’s not well, your grandmother. You know this, but you don’t want to accept this. You think about how proud she is, how she never has a hair out of place. She’d hate for anyone to see her without her carefully drawn eyebrows and red lipstick, wearing a scratchy hospital gown. Your grandmother loves to pose for pictures; she was married to a photographer. Because of this, it was always important to her to be camera ready. You do your best to make her pretty.

Your mother has moved your Nana from the hospital to a private room in hospice. You and your aunt sleep on the floor in her room that first night, waking up every few minutes to check on her. In the night, your grandmother tries to lick her lips, and you run out of the room to find a nurse. Water, you need water. While you hold the straw to Nana’s lips, you fix her wig. Her eyes stay closed as she drinks. She takes two impossibly tiny sips, then no more. You want her to drink the whole glass, in big gulps. You imagine going to the nurse and saying something like “my grandmother sure is thirsty today.” You want this more than anything.

Instead, a nurse with the kindest voice you’ve ever heard, gives you a pamphlet about the end of life. You devour the entire document, reading passages over and over. You convince yourself she’ll recover. The nurse’s shift ends and you say you’ll see her the next time she works, which will be in two days. She pauses and looks at you like she’s trying to gauge your frailty. You don’t look her in the eye, so she says goodbye and gives you a hug before she walks out the door. You call your husband from outside the chapel at the hospice and ask him if your grandmother will pull through. He pauses for too long before saying "I don’t think so, honey," and you know it's the truth, but you hang up on him anyway.

That night, her last night, you and your family sit at her bedside, play Sam Cooke on compact discs, and eat strombolis. Her sister calls to say goodbye. And just like that, she stops breathing.

We call the nurse, and we sit and watch as her heart stops beating. and we sit in stunned silence.

A lifetime wasn’t enough.

You and your family bathe your late grandmother, readying her for the funeral home attendants. Someone must have told them. The nurse, of course. She must have made a discreet call while we tended to Nana. Two attendants (one early twenties, one middle-aged) come in to take your Nana away from you, and you want to run screaming down the hallway, but you won’t leave her. Not now.

The attendants pick your grandmother’s body up and her wig slips to the floor. You realize you’ve never seen your Nana without her wig. Her hair is thin, wispy, and white. This is wrong. All of it's wrong. One of the attendants, the young one gasps and turns to his partner. “I’m not touching that,” he hisses to his coworker. You want to scream, but you don’t. Your sister, always the strongest one, reaches down and grabs Nana’s wig. The two of you position it on her head and glare at the younger attendant, who has the good manners to look embarrassed by his outburst.

They take your grandmother away in a hearse, and you follow behind in your car for a while. Eventually, the hearse goes straight, and you turn, and it’s like someone tore your spirit away from you.

Nana is gone and for a long time, it hurts to think about her. Everything that happens in the world now, happens without her. For a long time, it’s unbearable. One day, you start looking through family pictures, and you start counting Nana’s wigs. You make it up to 12 before you stop. You miss her, and you always will.

You isn’t you. It’s me. I still don’t like Batman. I prefer other candies besides M&M’s. I’ve often wondered about the funeral home attendant who didn’t recognize my grandmother’s crown when he saw it. All he saw was hair. But I saw more than that. I saw her. For just a moment, if only for her sake, I wanted him to see her too. I wish, when my mother was making funeral arrangements as my grandmother lay in the hospital, someone at the funeral home would have taken a moment to ask about Nana’s pride, about her signature. About how Nana wanted the world to view her. Because my Nana? She knew a thing or two about looking good.

About the Author

Erica Gerald Mason is an Atlanta-based freelance writer and journalist. Erica’s articles have appeared in People, The Wall Street Journal, Serious Eats, Byrdie, Vanity Fair and more. Connect with Erica on Twitter at @ericapretzel or on Instagram at @erica.pretzel.